The following article appeared in Slate last month. It was so insightful that it’s worth bringing to the top of the inbox.

Sex Offender Laws Have Gone Too Far

On Oct. 22, 1989, 11-year-old Jacob Wetterling was kidnapped while biking home from a convenience store. A masked gunman approached him, his brother, and a friend, and ordered the three boys off their bikes. After demanding to know their ages, he ordered Jacob’s brother and the friend to run into some nearby woods and threatened to shoot them if they looked back. The boys ran. By the time they turned around to see what had happened to Jacob, he was gone. Nearly 25 years later, Jacob remains missing, and the identity of his kidnapper is unknown.

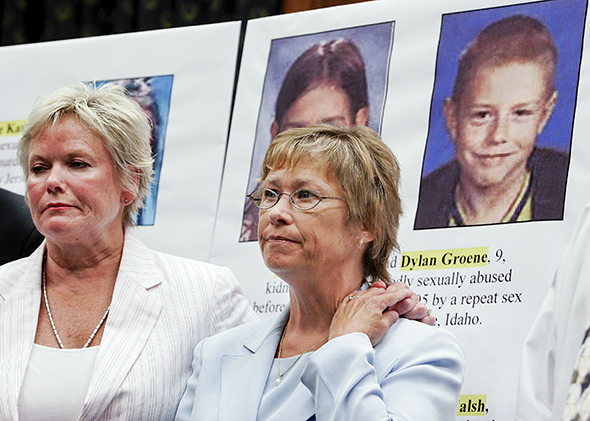

“I was a stay-at-home mom,” Patty Wetterling, Jacob’s mother, recalled over the phone last month. “I knew a lot about parenting, but I knew nothing about sexual abuse of children.” Determined to educate herself, Wetterling became “a sponge, trying to learn anything about this problem.” Soon, one thing stood out: Minnesota, where Jacob had been kidnapped, did not have a database that might help the police identify a list of potential suspects. Other states, such as California, had been keeping sex offender registries for decades. Wetterling also learned that Congress had never tried to craft a national approach to sex offender registration. She was determined to change that.

The result of her efforts was the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act, signed by President Bill Clinton in 1994. Jacob’s Law used federal dollars to push every state to create a registry. It worked. Today, all 50 states and Washington, D.C., have them. Since then, Congress has also passed several related pieces of legislation, including two major statutes. Megan’s Law, enacted in 1996, required that the police give the public access to some sex offender registry data, such as an offender’s name, photograph, and address. In 2006, the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act toughened the standards for who must register and for how long, and it upped the consequences of registration by requiring, for example, periodic in-person visits to police.

The upshot, experts say, is that the United States has the most draconian sex registration laws in the world. As a result, the number of registrants across the nation has swelled—doubling and then doubling again to 750,000—in the two decades since Jacob’s Law passed, according to data collected by the Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

Is the American approach to sex registration working? Who goes on the registries, for how long, and for what kinds of crimes? Do the answers suggest that they are helping to keep kids safe—or sweeping in too many people and stoking irrational fears?

In seeking answers to those questions, over the last several months, we were surprised to find that one of the sharpest—and loudest—critics of the ballooning use of registries is Patty Wetterling. “These registries were a well-intentioned tool to help law enforcement find children more quickly,” she told us. “But the world has changed since then.” What’s changed, Wetterling says, is what science can tell us about the nature of sex offenders.

The logic behind the past push for registries rested on what seem like common sense assumptions. Among the most prominent were, first, sex offenders were believed to be at a high risk for reoffending—once a sex offender, always a sex offender. Second, it was thought that sex offenses against children were commonly committed by strangers. Taken together, the point was that if the police had a list, and the public could access it, children would be safer.

The problem, however, is that a mass of empirical research conducted since the passage of Jacob’s Law has cast increasing doubt on all of those premises. For starters, “the assumption that sex offenders are at high risk of recidivism has always been false and continues to be false,” said Melissa Hamilton, an expert at the University of Houston Law Center, pointing to multiple studies over the years. “It’s a myth.”

Remarkably, while polls show the public thinks a majority, if not most, sex offenders will commit multiple sex crimes, most studies, including one by the Department of Justice, place the sexual recidivism rate between 3 and 14 percent in the several years immediately following release, with those numbers falling further over time. Which number experts prefer within that range depends on how they define recidivism. If you count arrests as well as convictions, for example, the rate is higher, because not all arrests lead to convictions. And if you distinguish among sex offenders based on risk factors, such as offender age, degree of sexual deviance, criminal history, and victim preferences—instead of looking at them as a homogenous group—you may find a higher or lower rate. Rapists and pedophiles who molest boys, for example, are generally found to have the highest recidivism rates. Nevertheless, the bottom line is clear: Recidivism rates are lower than commonly believed.

And in contradiction of the drive to crack down after a random act of sexual violence committed by a stranger, the data also shows that the vast majority of sex offenses are committed by someone known to the victim, such as a family member. In the case of child victims, that number climbs closer to 93 percent. In other words, Jacob’s case and others like it were terrible exceptions, not the norm. And yet, “It’s become a part of our culture that there are predators waiting around corners,” Hamilton said.

Wetterling remembers watching this spiral of fear after Jacob’s disappearance. “The fear was real. It was devastating,” she said. “People became absolutely terrified. There were people in my community who wouldn’t let their children bike anymore or play in the park.” Twenty years on, she has come to see this reaction as “not information-based.” And two decades after she succeeded in persuading Congress to pass Jacob’s Law, she’s now asking people to take a second look to see whether laws like the one named for her son are doing more harm than good and should be curbed.

Looking for data to explore this issue, we found that the best sources were Human Rights Watch, the American Bar Association, and the Government Accountability Office. Most of the data we’re using is culled from their reports. In a series for Slate, we’ll spotlight three areas in which the growth of registries has been unexpected—and, we suggest, unwise:

- Outlier offences. These are crimes far removed from the violent felonies that Jacob’s Law focused on, but which now trigger registration in many states. (Even public urination now qualifies.)

- The expanded duration of registration. States are keeping people on longer and erecting more barriers to getting removed from the list, even if one poses a low risk of reoffending.

- Collateral consequences. The range of restrictions attached to being identified as a sex offender has also grown. (In one state, you can’t be a sport fishing guide.)

Recent Comments